The global shipping sector rebounded strongly from the pandemic in container and dry bulk shipping. A lack of capacity to handle the unexpectedly strong wave of demand and Covid-related closings disbalanced global supply chains and led to spiking tariffs. In the first few months of 2022, the situation started to improve especially in clogged American ports, but the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the return of lockdowns in China has caused disruption to trade and global shipping. Consequently, supply chain problems are expected to drag on through 2022 and capacity pressures will continue.

Market outlook for shipping volume weakens as war weighs on economy

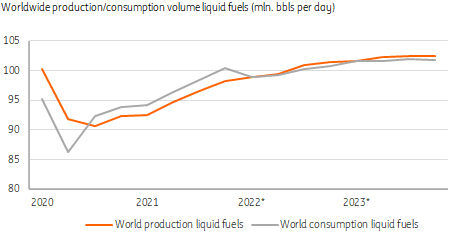

Uncertainty around the unfolding war in Ukraine is significant and is clearly impacting the global economy and world trade. After a double-digit bounce-back beyond pre-pandemic levels, we expect headwinds to leave trade growth limited between 1% and 2%, in our base case. With 80-90% of world trade travelling by sea, this also paints the picture for shipping volume in 2022. However, the differences in dominant good flows are significant.

Grain trade under pressure in 2022, oil trade in recovery

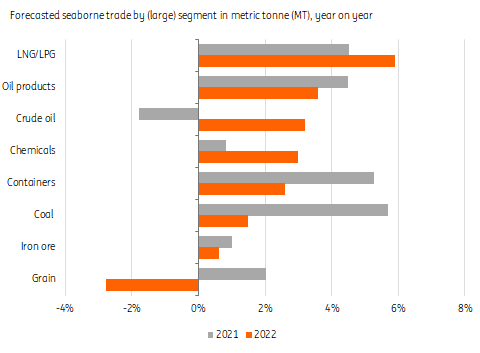

Growth in most segments in 2022, except grain

With resumed travelling and lifted Covid-restrictions in most of the world, energy product flows are expected to rebound and expand the most compared to last year, although the effect of the war and releasing strategic oil reserves influence growth. With the efforts to replace piped Russian natural gas with liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Europe, LNG/LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) tankers are expected to benefit the most (see box on LNG below).

Dry bulk flows are expected to show limited growth this year, and after a strong year for industrial dry bulk and rebuilding stocks (especially in China) 2022 will be more moderate. The comeback of coal as a source in the power sector following the surging gas prices will continue in 2022, leading to continued growth. Grain production is suffering heavily from the war in Ukraine, which is involving two of the world’s largest exporters, and alternative supply won’t completely offset this setback.

Container shipping growth will probably end up below trend in 2022 as demand for goods will probably soften with consumer spending in services sectors returning, purchasing power suffering from higher prices, and raised transportation costs. Uncertainty is clearly there, but global port figures for the first months of 2022 indicate a positive start.

Global bunker fuel prices in shipping close to all-time highs in the first months of 2022

War in Ukraine has multiple implications for shipping

In the general transport and logistics piece, we discussed the generally negative impact of the war in Ukraine. But this event has significant specific implications on direct costs, operations and business (good flows) for global shipping as well:

Direct costs

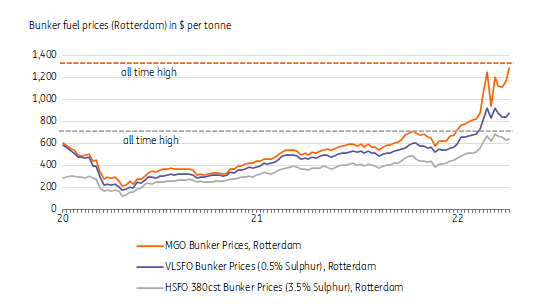

Bunker fuel prices and fuel price spreads are close to record highs

Bunker prices make up a significant part of total operational cost in shipping and the sector is one of the most energy-intensive industries. The fuel bill can easily exceed half of the total operating costs for larger vessels. Fuel prices are trading at double the 10-year averages for heavy sulphur fuel oil (HSFO) and have approached 2008 highs for marine gasoil (MGO). The fuel spread between HSFO and very low sulphur fuel oil (VLSFO)/MGO widened, which strengthens the case for use of HSFO which is only compliant in combination with installed scrubbers. Upward price pressure will also remain for some time to come.

The impact on shipping companies is unequal. Vessels operating under charter contracts can easily pass on the fuel bill to the charterer. But ships operating on the spot market (voyage chartering) usually carry their own fuel bill and they try to get this compensated in the rates. Still, there may be a mismatch. Container liners can apply bunker adjustment factors, but have refrained from pushing the full bill through via surcharges (bunker adjustment factor, BAF), possibly because rates are still much higher than usual.

Operations

Additional port congestion specifically in ports like Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg and Bremerhaven due to the suspension of Russian destinations by large carriers including MSC, Maersk and Hapag Lloyd, and extra customs checks. Large amounts of dwelling containers led to extra terminal inefficiency and delays in vessel capacity.

Banned Russian vessels from ports of several countries including the EU and UK. Vessels under the Russian flag make up 3% of the global fleet (approximately 2,850 vessels) and 0.5% of total deadweight tonnage (DWT), but there could be more under Russian operation.

Additional labour challenges (seafarers). Russia is the second-largest home country for seafarers after the Philippines. Together with seafarers from Ukraine, this makes up 15% of the global workforce (10.5% + 4%, respectively). This could also lead to operational challenges with absence and travel difficulties because the sector is also still dealing with the legacy of the pandemic with more people on leave.

Demand – good flows

Substitution in energy sources. Europe wants to reduce its pipeline natural gas dependency on Russia as soon as possible. Ramping up LNG sourcing is part of the solution. Temporarily switching (back) to coal in the energy sector is one way to reduce gas consumption and this already happened as a result of high gas prices. This leads to more shipments of coal, which we will witness in coal handling ports like Rotterdam.

Weakening trade perspectives, but mitigating effects from re-routing. The general trade outlook has deteriorated because of the war, but there are also mitigating effects as commodity flows are being redirected and routes are reshaped which is expected to turn into more tonne miles. How this plays out for shipping companies largely depends on specific markets and contracting. On balance, this is expected to create an average of 1%-1.5% extra fleet deployment in 2022, with the most impact on coal and oil products. Below we take a closer look at the replacement of commodity flows running from Russia to Europe.

More (super) slow steaming could be a logical reaction in shipping further into 2022 and 2023 once the market eases. According to DNV, up to 30%–35% less fuel is used when speed is reduced by 20%, and 60%–67% less when the speed reduction is 50%. This is significant and the average speed can still be lowered. However, speed reduction comes at a cost. As the transport capacity of the vessel is reduced, its earning capacity also declines. But it also may push up market rates.

Sanctions following the Russian invasion lead to a shift in shipping routes

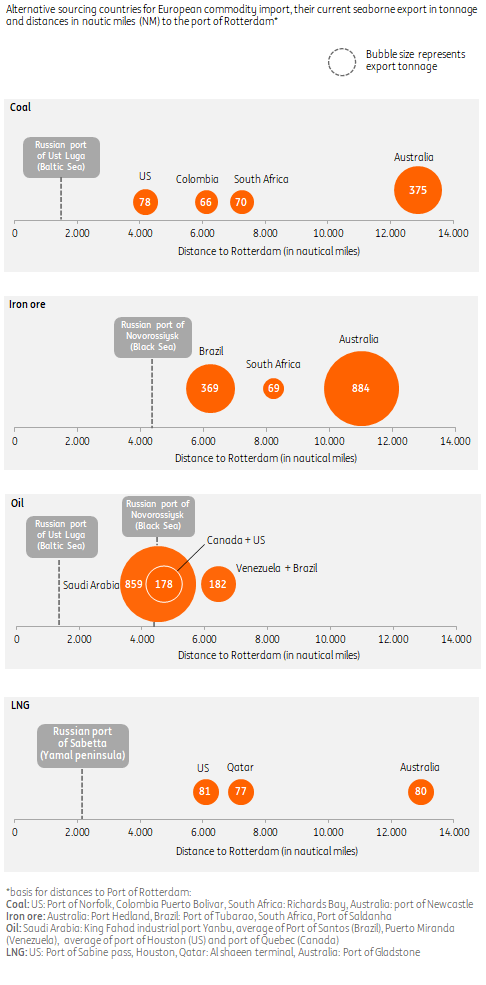

Russia is an important supplier of energy carriers and raw materials predominantly shipped through seaports on the Black Sea and Baltic Sea. A large share of these commodities will likely be sold to countries elsewhere in the world. We take a look at the most important European import categories from Russia:

Coal (EU + UK imported 87 million tonnes in 2021) is the dry bulk flow to Europe most exposed to redirection in the short run. The EU sourced 46% of its coal imports from Russia and from August onwards these imports will be banned. Alternative imports are expected to come from the US, Colombia, South Africa and Australia (China still has a trade ban on Australian coal). For most imports, this requires significantly longer voyages than the trip from the Baltic Sea.

Iron ore (EU + UK imported 108 million tonnes in 2021) from Russia to Europe is only a tiny flow, but other metal and steel product imports are also restricted.

Oil (EU + UK imported 172 million tonnes in 2021) Western countries have considered Russian oil bans, and oil majors like Shell and BP, as well as the world’s largest trader Vitol, decided to (gradually) step out of Russia and Russian oil. Russian (Ural) oil is generally of heavier quality, which could alternatively be sourced from the Middle East. On the other hand countries like India and perhaps China are likely to import more Russian oil. This will lead to substantial shifts in trade flow patterns in tanker shipping and more tonne miles.

LNG (EU + UK imported 78 million tonnes in 2021). Almost a fifth of European imports came from Russia in 2021 which will try to be replaced by US exports.

Substitute supplies for European commodity imports from Russia need to sail a longer way

Fleet expansion remains limited in 2022 across shipping sectors

Another important factor for shipping markets is the new vessel capacity. In the years prior to the pandemic, orders for new vessels slowed for bulkers and tankers. In the tanker segment, in particular, most new ordered vessel capacity is expected to come online in 2022 (40% of the order book for bulkers and 60% for tankers, leading to a fleet expansion of 2.8% and 3.5% respectively). In container shipping there has been a wave of new orders over the last year, however, only 3% of the current fleet size will come online in 2022. All in all, fleet expansion will remain limited across shipping segments in 2022 so this won’t derail the markets from the supply side.

Energy transition pushes retrofitting and scrapping

Normal demolition will cover some of this (1% on average across all segments). Higher fuel efficiency requirements (IMO EEXI efficiency measures for existing vessels will come into force from January 2023) and the shift to alternative fuels (current order book includes methanol (ready) vessels, for example) is also expected to lead to more retrofitting and more scrapping over the rest of the decade.

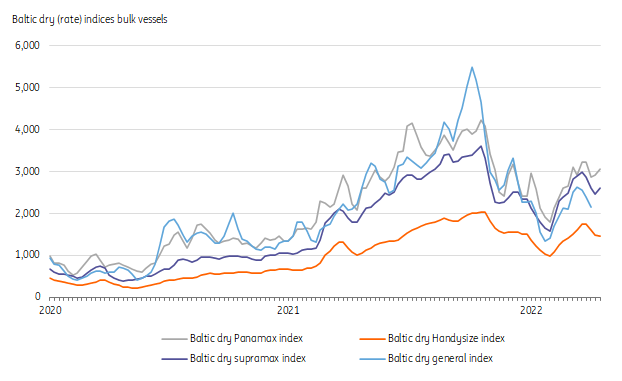

Dry bulk rates still significantly higher than pre-pandemic with medium size bulkers most attractive

Dry bulk shipping: beyond the peak, landing softly

The dynamics of dry bulk shipping are very different this year. The war in Ukraine has led to changing currents in bulk flows like grain and coal. At the same time, massive imports of iron ore from China have eased after a strong industrial driven rebound. The Chinese PMI indicates stabilisation in the first months of 2022 and its zero Covid-policy remains a risk. Consequently, raw material trading will weaken this year. Average seaborne dry bulk trade growth (excluding containers) may stick just above 0% year-on-year, but is expected to show growth in terms of tonne miles, as explained earlier.

Shipping rates for bulk freight passed their 2021 spike, but still trade above double their pre-pandemic levels in April 2022, which is an encouraging sign, although high bunker prices obviously also push up rates.

Tanker trading flows expected to see year on year growth through 2022

Better fundamentals in tanker shipping

Tanker shipping companies have been operating in difficult market circumstances since the second half of 2020. The market suffered from the setback in travelling during the pandemic. After the oil price recovered and floating storage was curtailed, the tanker market went through a phase with unusual low spot and charter rates. This year promised a more sustained recovery in oil demand, and reserves are relatively low, which should improve market fundamentals for tankers. But the war in Ukraine and surging oil prices has also created renewed uncertainty around future oil consumption. Although crude oil trade is expected to stick below pre-pandemic levels, oil and oil product volumes could see an increase of 3-4% with tonne miles going beyond that level because of the reshaping of Russian oil routes (Russia covers 12% of global seaborne oil trade).

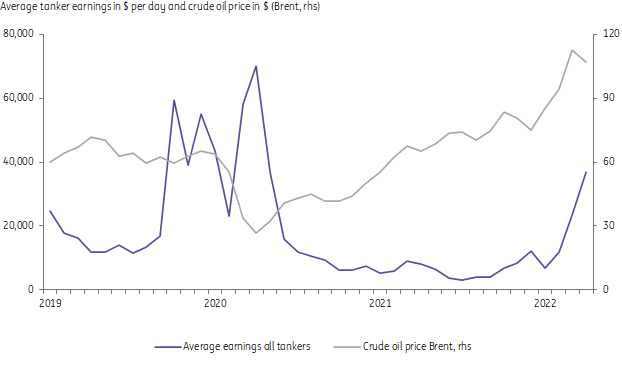

Tanker spot rates in recovery while oil price surge

Tanker rates leave the worst behind in sanctioned market

The resumption of travelling in combination with (self-imposed) sanctions following the start of the Ukraine war tightened tanker markets. Average earnings of all tankers passed its 10-year average for the first time since mid-2020 in April after a weak winter season. Rates for routes to the Black Sea (including Russia’s largest port Novorossiysk) and the Baltic Sea climbed particularly strongly as a reaction to the war and reluctance to sail to Russian ports.

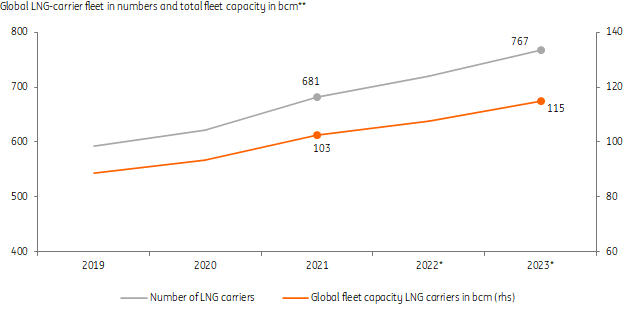

LNG-fleet expands, but will struggle to keep up with extra (European) demand

Replacing Russian gas offers opportunities for LNG shipping

Several European countries are highly dependent on Russia for natural gas supplies and are rushing to reduce this dependence. The European Commission aims to replace a third of its Russian gas sourcing 50 billion M3 (bcm) per year (33%) by geographical diversification of LNG sourcing. And on top of that, Russian LNG supply has to be replaced. Some European countries have spare re-gassing capacity and also plan to expand current capacity and/or build new terminals like Germany in Wilhelmshafen and Brunsbüttel. In the short run, countries like The Netherlands, Germany and France are also considering the opportunity to create floating LNG terminals to create extra capacity. The US already committed to ramping up deliverance to Europe by 15 bcm per year in 2022 and 50 bcm in 2030. In addition, the US, Qatar and Australia could possibly supply extra LNG, although spare supply of LNG on the spot market is limited.

The shift from pipeline to sea will lead to an extra push for LNG shipping demand over the following years. The global fleet of LNG carriers had a size of 681 in 2021 and 200 more vessels are on order. Constructing all these LNG tankers however will take several years. In 2022 and 2023 only about 8 bcm of additional capacity will come online. If we take an average of seven loops per vessel per year, this would offer an extra annual capacity of 54 bcm on a global scale by the end of 2023.

The combination of limited extra supply and limited extra shipping capacity means that the ability to ramp up imports of LNG flows is limited in the short run. There might also be some reluctance to invest in a 20-year term as LNG isn’t a sustainable low carbon energy source in the long run.

Source: hellenicshippingnews.com

.png)